PAST NUMBERS

#00

EDITORIAL

FROM SURREALISM TO THE DECONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

Artscape

TEXT

THE MINIATURE AND THE MODEL, ON THE PAINTINGS OF JOCHEN KLEIN

by Douglas Ashford

FROM OUTSIDE

TO SAY OR NOT TO SAY OR SAY IT ANOTHER WAY. ULRIKE OTTINGER’S FUNNY BOOKS.

by Ángela Sánchez de Vera

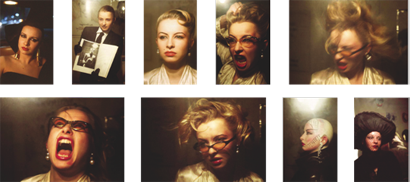

Photos in the context of Ticket of No Return (1979)

*Images extracted from the website www.ulrikeottinger.com

When I was a child I loved to read books that I did not understand. Enormous books, the thicker the better. Over time, when I began to understand what they were saying, I tried to renew the game with more gimmicky books, books on philosophy, books in other languages: English and German were the best. The pleasure laid in understanding a little, just enough not to be missed, but not so much as to run its pages. It was not so much to decipher strange thoughts as to populate the margins with my imagination: in any case, speed was the enemy. I've always liked dreaming while reading, it is something that has never ceased to seduce me and that certainly pushed me towards contemporary art. And if I remember this childish game, it was just to show you that I have found in Ottinger’s work a good reminder of those pleasures.

First approach: travelling to Valladolid

I do not think Ottinger’s cinema is incomprehensible, just slower. You might encounter her work as I found myself with it, getting a fragment that is fascinating but does not warn you of the complex load bearing attached. I ran into one of her photographs in an art magazine, playing as a film still and an advertisement of the visit of her work to Spain. The piece was suggestive enough to go examine one of these exhibitions closer, in a cold and beautiful Castillian city, under the promise that I would find another cinema.

I entered into the Museo de la Pasión behind the dual promise of several artists’ books and more pictures, as terribly perfect as advertised. I can only say that the exhibition was in a sense unexpected: in the old church, under an old architecture, I found an exhibition staged with ethnographic criteria: untouchable books in glass cases, some films and projections of documental slides. They were not only stylized and baroque images, as expected, but faces and landscapes from the taiga. I went looking for a perfect picture and I found myself in a whirlwind that I did not understand, a complex world that has been opening, slowly, from that first encounter. Two things became clear: the misunderstandings that can lead the advertisement of conceptual art, and the inexplicable certainty that Ottinger was not working in just cinema.

In fact, a third thing was clear to me: the need to start an informative task on that strange work because, although the trajectory of Ottinger is not as marginal as it is often written (her work has been showed in the best museums of the world), it is quite unknown outside artistic circles. This situation is not surprising because the difficulty to see her movies, accessible only in festivals and almost without commercial distribution in domestic format. I would like nothing more than if this article was for you the first reference to her work, and that its reading will awake your curiosity enough to visit her website, travelling at your own risk for its careful and abundant documentation.

In the U.S.A. you also have an extensive monograph of her work by L. A. Rickels, entitled The Autobiography Of Art Cinema, an extensive monograph not because it has many pages, but because Rickels has doubled its size by wrapping the description of her movies with several psychoanalytic and academic ramblings. While the book had not lost interest with half of its length, Rickels’ approach subtly plays the same game played by Ottinger in her work, surrounding the description of films, photographs and plays with idle, excessive meanderings of information. Between them spring ingenious comments that illuminate their understanding, key thoughts that were virtually unnoticed during the direct viewing of each piece. Those flashes are not critical findings a posteriori, but issues raised by Ottinger herself in her interviews and work.

Second approach: elusive identity of the things or Madame X

In Madame X: An Absolute Ruler, Ottinger staged a journey of a group of women who come to call for a new life, who are shipped to leave insufficient habits behind but end up falling under the yoke of a dangerous pirate who enslaves them aboard the Chinese Orlando. The new crew will be dropwise executed as they were discovering the secrets hidden by Madame X, which sustain her power to dominate. Revealing the fascination ended the uncertainty, it ends the power. Only the mistake kept them alive, dominated but alive.

This brief synopsis is not the only possible synopsis of the film. Nor does it reflect the play of identities that overwhelmed the spectator from the very title, Madame X, which hides the identity of the main character. The ship names the metamorphosing Roman by V. Woolf, the characters are doubled (Madame in the ship’s figurehead; actresses back to the boat, with the same body and other identities after being killed) and confusion reigns until the point that, following the initial call for women’s liberation, Belcampo arrives, a woman with the body of a man, who is subjected to a test to define her genre: only giving nonsensical answers to the nonsensical questionnaire demonstrates that she can be accepted onboard.

The misunderstandings and mistakes multiply in the movie, the first feature film by Ottinger, and this confusion remains. Throughout all her filmography, we witness constant metamorphosis, echoes and mirror reflections, as they finally define the development of the characters. Usually Ottinger splits their identity: Dorian Gray is interpreted by a woman who plays a man in Dorian Gray in the Mirror of the Yellow Press, a character who watches himself, as another avatar, at the opera stage. Like the character Orlando, quoting Woolf again, who changes name, attributes and century on each of the five stations of Freak Orlando, without changing his/her body... one character can be incarnated in different bodies and one body can be used to play different characters, different eras, different desire projections.

Ottinger does not build characters but archetypes, nor shows actors but bodies that shape default behaviour. After that, she puts them into reality, where they can be watched in motion. It is terrible, from this perspective, to attend the arrival of a perfect woman "created like no other, to be Medea, Madonna, Beatrice, Iphigenia, Aspasia" who lands in Berlin or, as announced on the airport speakers, in "Berlin-Tegel-Reality-Berlin-Tegel-Please Reality." Announced her fate, only remains to witness her suicide, following her through the nocturnal geography of this (so) real city. And once again, this fast approach to the fabric of Ticket of No Return is not given naked to the viewer but tangled, without liability, along its length. It is difficult to reach all levels covered in her films: dropping the most obvious interpretations, there are still others that need to be read: the images on the screen are footnotes of a deep story that will only be decrypted from the book.

I searched for the advertisement of Ottinger exhibitions and I found this one. I can´t quite remember but I am quite sure that this was not the background image that I saw. (Exit #19, 2005)

Books on Carnival

Madame X is the first feature film by Ottinger and one of her few films with an edited script: Ottinger has published, in facsimile reproduction, only three and a half of her scripts, but every film she has shot started with a research book.

These books are not usual scripts but big notebooks which store all kinds of graphic issues for years. Its pages hold readings, rehearse dialogues and construct the "images" or mises-en-scène which will be later developed in the films. Ottinger presents these scripts, these artist’s books, when seeking funding for each film. They are shocking when compared with standardized scripts that manage in productions. In fact there is not a model or an unique prototype of notebook: scripts published are different, with exclusive sections (costumes, dialogues) within a basic outline in common: a first set of ideas and the schedule for filming.

It is clear that these books base their aesthetics in collection, in a selective and thoughtful accumulation that will build later in each film. What is perhaps not so obvious is that they are dominated by a certain childish aesthetic. The use of allegory drives them (between the characters of Madame X we find a Graduate Psychologist, a Chinese Cook, an Alcoholic Housewife ... defined with the simplicity of the stories for children) and so do the aim to rebuild cinematic genres (pirates, vampires, Far East...), genres steeped in childhood or in the ancient and primary stadiums (more naive) of spectacle. The intense colour treatment, the taste for saturated contrasts, the costumes and parades take us back to childhood. It reminds me of the film Arrebato (Iván Zulueta, 1979), where we are invited to follow the main character on the filming of an absolute movie, an activity that allows him to feel again the intense experience of contemplating artificial images (stickers and illustrations) as when he was a child. Greenaway also tried to reproduce childish illustration aesthetics in Drowning by Numbers (1988), filming intense pink and black sunsets, bright calm nights and tiny miniatures. Greenaway and Ottinger not only share the quest for a childish intensity that stylizes their photography: both mix books and cinema, although they do it in different ways. Both publish books that help in reading their movies, but Greenaway skips all barriers and films the book directly, paints words on the actors and the film. In the case of Ottinger, the connection is not so literal.

Ottinger’s books light the plot of each film and, above all, help to understand the nature of their images. The scenes of her movies, like the collages and “images” of her books, are basically living pictures that keep the time of the painting, a time for contemplation and not development (just movement). They are tableaux vivants, in the stele of a long cinematic tradition, but rather still than vivants. Those amazing photographs that I saw at first, although they promised violent actions, were frozen when I saw them in motion. Their potential energy never explodes, just gives energy enough for parading... so the documentary photography ended up being misleading too: Ottinger’s films are full of easily identifiable equivocations (actors who act under other genres) but also play with more subtle confusion. There is no indication when a section (or chapter) begins and ends in Freak Orlando: the light is the same, the actors are the same... there are no marks, no cuts. These changes would have been ostentatiously treated in Greenaway’s work: altering the light of the scenes, interspersing posters or drawings before their opening, or painting on the film. The homogeneity of her no-graphic photography contributes a little more to increase the confusion.

Beyond cinema

I have suggested that the work of Ottinger is the work of a conceptual artist, a nuance that is useful for understanding why her cinema moves away from the cinema and closer to pure narrative: Ulrike Ottinger was born in 1942, the same year as Peter Greenaway and Lawrence Weiner, among others. She belongs to the generation of conceptual artists, a generation that was trained in traditional fine arts which they were gradually abandoning, with great regret, knowing that the complexity of their environment and their dreams needed another form of articulation. They found that this aim passed through the inclusion of narrative in art and started to connect different fields and mediums.

Ottinger came to cinema from painting, photography and performance. After working several years in Paris, a deep crisis pushed her to abandon etching and painting as a static and fragmented media, unable to contain her stories. Back in her hometown, where she ran a contemporary art gallery and a film club, she began to think about making cinema via making funny books. When she began to direct, in the seventies, she was just testing a new archive, a wider media that allowed her to keep all her world together: photographs, readings, thoughts. Then, the art (as object) acquired value becoming theatrical, a prop capable of acting on her cinematic mises-en-scène.

Ottinger never stopped making art for making cinema, and that is why her movies can not be understood just as cinema. It is possible, in fact, that Ottinger had not made movies, if we compare her work with the television narrative in which we are educated, a twin narrative of advertising: clear, linear and economical. Ottinger only makes cinema when we compare her work to the cinema before cinema, before it was reduced by industry (and even more by television). Alternatively, we can compare it with a cinema after cinema, an expanded cinema, as Greenaway calls it using the R. E. Krauss terminology. It is a cinema that is not autonomous: the photographs that she makes "in the context" of every film are not autonomous, their books, of course, are not autonomous either. Not even the movie itself is autonomous: it is only a part of that broader narrative media called cinema. Book and movie spin together, trying to tell stories as deeper than they need to be sewn together to get on their feet. The story only would be complete when we can read the joint archive, giving it the time that needed.

Some kind of misunderstanding

The reading of these books will not solve the plot of her movies as if we had found the clue to the crime: just extend its many references. I realize that it is very easy to misunderstand the work of Ottinger: she is eccentric, lives in her own world, and is terribly free. It is Ottinger herself who plays very consciously with tangles and misconceptions. She decontextualises ideas and myths, she uses the misunderstandings that arise in the friction of different cultures and social groups, and she tries to relive fragments from past, fragments that have lost their meaning today. It would be unfair to pass through all her world appealing to fantasy, as Ottinger has noticed when rejecting comparisons with the exuberant frames of the last Fellini. Everything is methodically stuck, methodically developed and methodically embroiled in her stories.

The book by Rickels that I have been quoting, quotes itself The Autobiography of Writing by E. Meyer. Following a simple slip of interpretation, this title could connect with The Autobiography of Alice B. Tocklas by G. Stein in the looking for similarities. After all, the book opens with a quote of hers. Both Ottinger and Stein hide their self-portraits in foreign stories, both use a direct, sometimes naive language and transcribe it so immediately, so personally, that often it is incomprehensible to the majority. Meanwhile Stein’s tour through several universities at the United States attributed her success to the fact that anybody really had read her work: people filled the auditoriums for the prestige of a dark oeuvre that no one had really addressed. It could be, but they could also come to celebrate her humour, her funny way to say or not to say or say it another way. There are big doses of humour in Ottinger’s work: you cannot forget it in stories that set up bizarre misunderstandings as a mean of camouflage, as creative strategy or as technique of seduction. Reality is stranger than reality, and it is necessary to reconstruct it to realize: her stories are of such a kind that invite you to sit down and to read and to talk and to argue and to dream and to laugh and to think. Take your time.

1 http://www.ulrikeottinger.com/en/index-en.html

2 Minneapolis/London. University of Minnesota Press. 2008

3 Ottinger has published three of her scripts: Madame X. Eine absolute Herrscherin. Drehbuch. Frankfurt am Main. Stroemfeld/ Roter Stern. 1978; Freak Orlando. Kleines Welttheater in fünf Episoden. Berlin. Medusa Verlag. 1981; Taiga. Eine Reise ins nördliche Land der Mongolen. Berlin. Nishen Verlag. 1993; and excepts from Dorian Gray im Spiegel der Boulevardpresse in 1983 and 1985, and few pages from Prater (2007), in its dvd edition. She also has got two unfilmed scripts: Diamond Dance (1991) and Die Blutgräfin (1998).

4 Her first script-book was Die mongolische Doppelschublade (1966).

© 2013 Angel Orensanz Foundation

CONNECT US