PAST NUMBERS

#01

EDITORIAL

TEXTS

FOR SALE

by Jonathan T. D. Neil

FROM OUTSIDE

ART AFTER (THE END OF) THE BANQUETS.

by Domingo Mestre

FROM INSIDE

ALL THE ART THAT’S FIT TO DRINK

by Noah Marcel Sudarsky

A friend of mine remarked recently on the latest pretentious practice which consists in not serving wine at openings. Alcohol is a staple at art openings, he noted, because a drink makes bad art palatable, and good art enchanting. Great art, of course, requires no chemical enhancement; it leaves the soul exalted. The viewer, faced with a truly compelling work, will leave a museum or a gallery uplifted (whether sober or not). Critics, artists, aficionados, and everyone else associated with what is being called “the art world” these days (in a rather End of Days strain) are looking for an adequate prism through which to contemplate their supposed fall from grace. Holland Cotter, in a righteous all-you-parasites-deserve-what’s-happening-to-you vein, has debunked the entire art world establishment (of which he is one of the more established members), and the reviewers who have supposedly made the lavish dinners and after parties that are/were apparently so ubiquitous the nexus of their “social life” (damn those pesky NY Times guidelines!). I haven’t actually experienced first-hand what Mr. Cotter was talking about when he said that (not much anyway), but certainly the “art world,” isn’t about to reinvent itself (along what lines? Mr. Cotter offers no suggestions), and I don’t feel like I need to recite any mea culpas. The Armory Show, that enduring barometer of art market health, defied the doomsayers in no uncertain terms, and recorded 70,000 more visitors than the previous year. 25% of galleries recouped their expenses on the first day, which was only the preview. So Mr. Cotter and all the other Cassandras can pretty much eat their hearts out. And as much as I wish I could say I’ve been feasting at the expense of Larry Gagosian, Jeffery Deitch—or anyone else for that matter—I really can’t. I have emptied a few glasses of cheap wine, though, and I certainly intend on draining a few more plastic chalices before the Apocalypse, or the Singularity, or whatever is going to happen in 2012 (whether or not I review any more art, I might ad).

Which isn’t to say changes aren’t afoot. A few weeks before Mr. Cotter published his scathing indictment, I wrote an article decrying the state of the art (which, as it happens, was the title the editor originally chose for the piece), as embodied by Damien Hirst and his carnivorous cataplasms. I suggested that the present upheaval would generate “avant-garde, eruptive, self-propelling and deeply heartfelt movements that will come to define our new era…” I proposed a term for one new trend in fine art, distinctly related to the outsider art that flourished during the Great Depression (of which more later). But back to the vino... The reason not serving any booze is arrogant, in my friend’s opinion, is that most art will not pass the sobriety test. It requires a modest booster from Dionysus to be viewed, if not always favorably, at least not completely negatively. And thus, the gallery owner who refuses to serve wine (you know who you are…) is setting the bar too high. Using my new-found critical prism, I will peruse some of the art I’ve seen around town, not just at openings and art fairs, but also in the course of my other cultural peregrinations (many of which also featured some drinking, I must admit). In the interest of keeping as many friends as possible so that I won’t have to drink alone at these happenings, though, I will talk mostly (though not exclusively) about the art which did not require more than a very modest alcoholic intake to leave a favorable impression. The “intoxication index” I provide in the following overview thus refers directly to the work at hand, and not to how many drinks I may have had at any given opening. To make sure of this fact, empirically, I made sure I actually looked at the works a few times, and was sober during at least one viewing. Thus, it is the art itself which is intoxicating here—or not.

When I first discussed the idea for this piece with Juanli, I thought my lens would be turned distinctly toward the work of unknown or little-known artists, because there is a real phalanx of talented individuals out there making thrilling art, who either don’t care or don’t know how to market themselves effectively. I thought it would be appropriate to give this anti-mercantilist phalanx a sounding board in the pages of an ambitious new publication. But while I still want to mention some of the more inspiring work by individuals who haven’t been co-opted yet by the system, I simply want to talk about some remarkable art. By that I mean art which stands on its own, regardless of the context in which it is being viewed, or of what Vik Muniz called “the process of enrichment” on which most art, these days, seems to depend. We were talking about Jeff Koon’s New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker (1981) when he used that term, a piece Muniz had selected for his MoMA Artist’s Choice Series, and the relationship to his portrait of Marlene Dietrich in Diamonds (Diamond Divas, 2004). When Vik first spotted the installation, at International With Monument Gallery in the East Village in the early eighties, he told me he hadn’t made the transition from advertising to art. The vacuum cleaners, superbly lit as they were in their glass case, made him realize that fine art and commercial art depend on similar display mechanisms, and on a kind of semiotic enhancement. Barthes called this idea the “mythologization” process, where the “myth” equals a semiotic system that is condensed into a distinct signifier. Barthes was attempting to devise a hermeneutic to codify what Ferdinand de Saussure had already intuited—a science of form, based not on content, but on signification—that is on the arbitrary nature of the connection between signifier and signified. “Diamonds are forever,” said Muniz, is a good example of how a struggling industry saved itself through a semantic adulteration (because diamonds, just like any other mineral, can be obliterated). And so, we are brought to Hirst’s avatars, diamond-studded skulls and toothy leviathans. The myth, be it visual or literal, is always a codification of form. But whereas Guy Debord, for instance, understood what Barthes was talking about on an organic level, and proceeded to break down and expose the perverse mythologies of consumer society, contributing to some of the twentieth century’s more dramatic socio-political upheavals (May ’68), less gifted thinkers strayed toward the specious and the doctrinaire. These encephalitic trapezists, (i.e. the Lacanians), with their inextricable circumvolutions and sophistic lexicographies, never offered a constructive prism, or really, for that matter, ever deconstructed anything that hadn’t already been decorticated by Bachelard, Barthes or Foucault. And, with the notable exception of Félix Guattari, no one has ever been able to really figure out what Deleuze was talking about anyway. The process of codification actually became one of quasi-permanent adulteration.

And so I must respectfully disagree with Vik Muniz. I think that art which usurps an advertising esthetic, or blurs the line between art commentary and artistic practice by inflicting a layered, post-indexical hermeneutic, creating a simulacrum, a staging of reality via the displacement of some pre-existing myth, does not rank highly on the intoxication index (which isn’t to say that approach does not provide unique gratifications).

Personally, I find the operation repugnant; but, exactly for that very same reason, I think that there is no better way of representing death in our time, in this case the death of art itself as a product differentiated from the rest of commodities. Doubts emerge at the time of asking oneself if other ways of thinking still fit. If there is still a place for thinking about art itself and for itself, after its postindustrial fall into pure financial speculation and the worldwide crisis of that speculation. Said in another way: Does anything else exist, in the business of Art, apart from money?

Thus, in the article originally known as “State of the Art,” I named a novel trend in fine art, one which is not driven by a referential element, or reifying constructs. I dubbed this movement “Supercraft,” and I was apparently on to something. In an article titled “The Art World Embraces Arts & Crafts at Armory Week,” New York magazine reported that the works with a crafty, home-spun feel were what sold best, by far, at the Armory Show—in part, no doubt, because just like the folk art of the thirties which supplanted the expensive modernist masters in many important collections, Supercraft tends to be economical.

Aristotle, in his Poetics, suggested that the audience knows instinctively when it is confronted with “truth,” as opposed to a factitious articulation, and science has comforted this notion. In Blink, Malcolm Gladwell demonstrates convincingly that the observable manifestations of human intuition, or instinctual knowledge, are perfectly mind-boggling. Kant, when he asserted that “a priori” notions actually constitute the fundamental building blocks of scientific theory and experience in general (including, of course, esthetic values), was in fact already making the same argument (because the number of observable facts at our disposal is infinite, a working hypothesis must be constructed on a kind of common sense pre-selection).

Nicola López, Untitled, 2009 graphite, gouache, ink, molding paste on paper, photolitho on mylar collage 18 x 18 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

And so, unlike, say, relational esthetics, Supercraft does not depend on Deleuze, Derrida, or any degree of epistemological stratification to tell us why it matters (which is why its intoxication index is so high). The work of Jim Drain is gratifying, for instance, because it jibes, because its polyvalent resourcefulness and its meta-medium combativeness meshes convincingly with the zeitgeist, and possesses a distinctive (that is, not a normative) weltanschauung. A postmodern appropriation strategy is unnecessary. I gave examples of Supercraft in my New York Press piece, and I’ll provide a few more here: Nicola López, whose vertiginous monoprints of falling, self-consuming cities seem to subsume the apocalyptic thematic into something much more subtle and intricate. Her polymorphous “Large Tangle,” which was visible at Caren Golden’s booth at the Pulse Art Fair, exploits what has become López’s signature pot-pourri of collated techniques. The work depicts a jumble of I-beams, ductwork, hemp rope, and various building materials, all interlaced in a yellow mylar loop. It is a woodcut print that also utilizes gouache, oil pastel, ink, litho crayon, graphite, and collage elements. Entirely eliminating the distinction between print-work, painting, and collage, López in effect creates her own unique, striking medium. Her next show opens at Caren Golden Gallery in Chelsea in May.

Equally appealing to me is the work of Alison Elizabeth Taylor. Her marquetry panels, which use wood-inlays to create casual scenes of everyday life in which the protagonists seem lost (she also constructs entire three-dimensional habitats, like Room, 2007) are an example of how a kitschy technique traditionally used in a folkloric vein can be turned on its head, to tremendous effect—fostering a psychic backlash. Her breakthrough show at James Cohan came down last summer, but a new marquetry panel, Bombay Beach (2008) is now visible in the Viewing Room at the James Cohan Gallery.

What makes this burgeoning movement so super thrilling is that no subject is off-limits. Sandow Birk, a Californian who shows locally at White Box (a gallery which recently abandoned Chelsea, where it resided in what was hands-down the most architecturally ambitious non-institutional exhibition space in NY, just a big concrete box), is another notable force in Supercraft. His enormous Depravities of War series of woodcut prints depict some of the documented atrocities of the Second Iraq War. He takes the notion of craft to its most essential, communitarian level by using assistants to help with the carving of his giant plywood blocks, actually encouraging them to inject their own personal drawing styles into the work. That approach is in no way antithetical to the Supercraft paradigm, which welcomes collaborative effort—but shuns alienated labor and mass production.

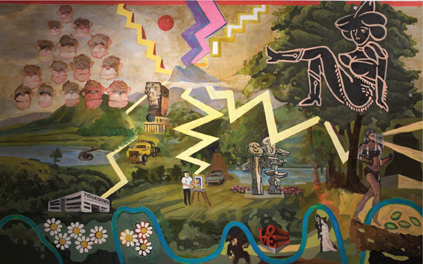

Jeremy Earhart, who recently closed at Goff + Rosenthal, is one of the most exciting exponents of Supercraft because he’s doing precisely the reverse of a Jeff Koons or a Murakami: Instead of shopping out the designed object to be created or reproduced in an industrial setting, he’s taking a manufacturing technique, in this case poly-lamination, and concocting unique hand-crafted one-offs. Earhart uses automotive paint, Plexiglas, acrylic sheeting, and monofilament line in his luminescent hybrid works (like the tentacular Rockets Red Glare, or The Thin Ice of Modern Life, 2008, which portrays an incandescent church bell ringing). It’s too easy to dismiss Earhart’s sculptures as poppy “club art.” His creations may have a psychedelic feel, but they are completely original. By merely layering countless sheets of hand-cut plastic, he creates cryptic shamanistic vessels, part 3-D Op art, part New Age bas-relief. The intoxication index of Earhart’s work is stratospheric. Supercraft practitioners, many of whom operate in an ostensibly outsider strain, are in fact firmly implanted in the larger symbolist tradition. Allegory is achieved through a convergence of scenic elements. As in a stream of consciousness narrative, symbolist art can generate analogical meaning, or germinate into pure Absurdism. The Bruce High Quality Foundation, with its triumphant “Empire” exhibition at Cueto Project, is one of the more exciting symbolist ensembles. Until now, it’s fair to say, American Art had only dabbled in Dada, the parent pauvre of symbolism. Too intellectual, too anarchical, Dada in fact constitutes the very antithesis of the pragmatic, utilitarian American tradition. It is Louis Bunuel trying to outgun John Ford. Even Jeff Koons, whose lineage to Duchamp has been widely trumpeted, is almost the antithesis of a Dadaistic artist. Readymade art never constituted the foundation of Dada. The soul of Dada is Absurdism; whether is it minimalistic and object-based, as per Duchamp, or densely surrealistic and painterly, as per Dali, is strictly irrelevant. But “Les Bruces,” as Valerie Cueto affectionately dubs this six-person agitprop ensemble from the fringes of Bushwick, are the real thing, a true Dadaist dynasty. And while they are famous for their video performance work, like their adaptation of Cats and their dystopian installations and models, like Pizzatopia, which depicts every NY neighborhood as a topping on a slice of pizza (unfortunately, you can’t buy a single slice, you have to purchase the whole pie), I was actually most partial to their 26-hand series of oils (for which friends, lovers, and family members were cheerfully co-opted), The Course of Empire (Consummation, Desolation, Destruction, pastoral, and savage). These referential paintings, sublimating individual ego, manage to incorporate a convincing, consistent hermeneutic. The series is explosive, and suggests a cataclysmic blueprint, a primal if tongue-in-cheek choreography of Biblical proportions—Paradise Lost meets Best Western. These anonymous paintings are an exhilarating, theatrical ode to extravagance and decay.

The Bruces High Quality Foundation,

The Course of The Empire (Pastoral) 2009.

Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 63 1/2inches/100 x 163 cm.

Courtesy of Cueto Project, New york.

Symbolism, which has been making a come-back, is well-represented these days. The Orwellian and only faintly Absurdist canvasses of Ian Davis visible at Leslie Tonkonow (also featured at Volta NY) make for a terrifying totalitarian panoply. The “Strange Geometry” exhibition boasted what was perhaps the most tightly executed and technically flawless painting to be seen during Armory week. Michelle Dennis, a young painter who had work up at DFN Gallery at the same time, is a symbolist in a more situationist strain. Her monumental, thickly-layered oil canvasses, depicting donkeys alone or grouped together, or even piled together in crushing monticules, are a psychic cry. The pieces all evoke crushing social forces beyond one’s control, and function as a searing indictment. Ian Davis’s pro-forma oils, like Estimate (2007) indicate a debilitating stasis, a paralyzing, quasi-permanent state of alienation, but the plight of the oppressed equines in Michelle Dennis monomaniacal works, like the triptych Evolution (2009) isn’t merely metaphorical. It makes the case for human revolution. The donkey was also the leitmotif in Karen Yasinsky’s “I Choose Darkness” exhibition at Mireille Mosler, which is based on Robert Bresson’s 1966 film Au Hasard Balthazar. Using stop-motion animation, Yasinsky has created a re-rendering of Bresson’s classic tale of oppression, with puppets (screened at MoMA in 2008). The Yasinsky show also features Mr. Magoo in a new drawing animation based on the woes of Balthazar the donkey, Enough to Drive You Mad (2009). Magoo is a metaphor of witless nonchalance (“I needed a character that was totally oblivious,” Yaskinsky told me). Yaskinsky’s work functions effectively as Po-Mo appropriation, and the polyvalent nature of the show (puppet animation, drawing animation, and painting) is clearly a testament to the transformative potential of the donkey myth and the artist’s own commitment to what the press release calls “the evolution of her subject,” but it lacks both the originality and the sheer compulsive force of Dennis’s work. The time of the donkey as a passive force has come and gone. These times call for new articulations, not complacent, hyper-intellectualized codifications. Distanciation is good for the indolent and the rich. In that sense, the group show “Talk Dirty to Me” at Larissa Goldston, featuring the usual suspects like John Currin, Lisa Yuskavage, Alex McQuilkin, and Rachel Feinstein, was just so nineties. The exhibition, a hodgepodge of tits and asses and witty formulations, à la David Shrigley, made the very idea of sex consternatingly trite and almost as ineffectual as the majority of the works which populated the gallery. Forget Holy Fire, forget the fact that the animus is still the antidote to most of our ontological woes, forget passion or debauchery even, what is the point of a series of tepid, sardonic works, be they referencing sexuality or anything else? Not all the art that constituted “Talk Dirty To Me” was bad, not by a long shot, but even the pieces by Currin and Sienna were problematic for their uncharacteristic lack of potency. For the record, Rachel Feinstein’s nude 2-D sculpture, a flat, multifaceted figure of a woman on her hands and knees (Orphan, 2009), was probably the most revealing, smartest work. Still, comparing this group show featuring some of the biggest and hippest names in contemporary art to (to give just one example) the retrospective of early super 8 works by Derek Jarman at X Initiative (a project spearheaded by Elizabeth Dee, at the old Dia Foundation space, visible through May), reveals a kind of accelerated decrepitude of the Id, or simply an oxidation of the modern-day imagination as it pertains to the founding principle, the Earth Mother (which, I suppose, considering that nearly all the artists visible at Larissa Goldston were weaned on the normalizing tsunami of cable TV, isn’t surprising). Jarmin’s filmic corpus became a catalyst for an entire generation because he had no real referential precursors outside of maybe Chris Marker and Godard, and had to invent his own codes. Barthes called this process “postulating significance.” And so Jarmin made Sebastiane (1977), perhaps the first film to openly represent gay sexuality. Conversely, the snarky nihilism of South Park and Family Guy contributes far more to the weltanschauung of the current generation of artists than the revolutionaries and visionaries of prior decades.

An artist who does do justice to the Earth Mother, and then some, is Australian prodigy Theresa Byrnes, whose “Revolution/Revolve” exhibition went up at Rogue Space just after Armory week. Her collage, assemblage, and tie-dye on paper techniques were a shift from much of the work of this prolific performance artist and painter, who triumphantly filled the Saatchi & Saatchi Gallery in New York three years ago with her gigantic abstractionist tableaus and panels. (Tracey Moffat paid her a vibrant homage that night). Boob Spiral, a mammarian vortex, and Boob Mobile, a cascading nebulae, as well as Time Ate My Mother and Boob & Penny Platter, all recontextualizing the Feminine Principle, with a galactic twist, while similarly using pennies, pences, pesos, and assorted currencies in an abstracted, cosmological vein. The work evokes quasars, resurgence, and the cycles of nature.

“To think within the boundaries of ownership and sale is narrow,” Byrnes remarked. “The great circle is moving toward another way of existing, for what is a coin but a fickle disk.”

With Byrnes, the shift to a dialectical mounting is already suggested—what Jacques Rancière considered the negative of the symbolist tradition, where elements dovetail, combining without particular violence (Derek Jarman’s works have a dialectical inflection as well, particularly his seminal Jubilee, 1977, and Blue, 1993). The dialectical framework, which utilizes a strategy of collision, friction and antithesis, is much less prevalent these days than the symbolist editing en vogue, but it was flagrant in the controversial work of Eugenio Merino, featured by ADN Gallery at Volta NY. Accoralado (2008), which represents a demented Dalai Lama wielding an AK-47, and Still Staying Alive (2007), a bronze of Osama Bin Laden as John Travolta, are certainly jarring, but the inherent incongruity functions as more than a cogent paradox; Moreno’s transgressive, paroxysmic sculptures constituted some of the most literate political art visible at any of the NY art fairs this year. And it proves that the whole intoxication index isn’t very significant after all, because encountering that rarest of artistic phenomenons—hyper-lucidity—is a strictly sobering experience.

Finally, I’d like to suggest that while the symbolic and dialectical mounting strategies identified by Rancière are still the two dominant conceptual vectors in fine art, there is a third possible editing strategy, the elliptical. Shreshta Rit Premnath’s Blue Book, Moon Rock (2009) installation at Thomas Erben Gallery is a testament to that third path, which is perhaps the most distinctly contemporary, or even avant-garde, of the three. Referencing Wittgenstein, Premnath juxtaposes various materials and mediums representing an aspect of the lunar landings, which don’t collate in a symbolic vein to create meaning or clash in any heterogeneous dialectical sense. He thus combines a photograph of a moon rock, a chalkboard, a screenprint, and the light from a reeling projector onto silver sprayed acetate which evokes a kind of shimmering, unknowable cosmological constant. The rock is re-imagined by the versatile parade of overlapping media, suggesting both the original, heroic impulse which brought us to defy our stratospheric limitations and reach into space, and the prosaic reality of the inevitably disappointing mineral manifestation which was returned to us. But really, Premnath isn’t making any point at all, merely hinting at the inherent, cosmic paradox that is life.

Note: Parent pauvre refers to a poor relative or descendent, not a progenitor or begetter.

#00

EDITORIAL

FROM SURREALISM TO THE DECONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

Artscape

TEXTS

THE MINIATURE AND THE MODEL, ON THE PAINTINGS OF JOCHEN KLEIN

by Douglas Ashford

FROM OUTSIDE

TO SAY OR NOT TO SAY OR SAY IT ANOTHER WAY. ULRIKE OTTINGER’S FUNNY BOOKS.

by Ángela Sánchez de Vera

VISUAL ARTICLE

FROM SURREALISM TO THE DECONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

by Dani Sanchis

FROM INSIDE

ART AND DECONSTRUCTION. CONSTRUCTION, DECONSTRUCTION AND THE PRACTICES OF CONTEMPORARY ART

by Derek Bentley

CONVERSATION

ROBBINSCHILDS. AT THE NEW MUSEUM

by Juanli Carrión

Artscape

WEB REVIEW

MADE IN OAXACA. Creating an Oaxacan ‘Other’ under multicolored tarps.

by Saúl Hernández

© 2013 Angel Orensanz Foundation

CONNECT US