PAST NUMBERS

#01

EDITORIAL

TEXTS

FOR SALE

by Jonathan T. D. Neil

I am for sale.

Perhaps this is a misleading statement. After all, me, myself, I am not for sale. My right to myself, as it is written, is “inalienable.” Even if I wanted to sell myself, I could not, legally that is. But my labor is for sale. What you are reading right now, the words on this page, they have been sold. This might make it sound as if the words themselves were sold, as if the words themselves had a value separate from what they signify, separate from the meaning they are meant to bear. But if my words alone had value, then I could say anything at all, and still get paid. “Crucial steam does cold circles when crowed roosters bark zero.” That will be $5.00 please. Talk, as the say, is cheap.

Writers do not get to work this way. Visual artists sometimes do. The great myth about Picasso at some Parisian café paying for his neighbors’ dinners with a sketch on a table check always illustrates the somewhat religious claim about artistic transfiguration, about how some artists come to wield the magic wand of value, making money by fiat, as if wine from water. I do not get paid for my words alone. It is what my words have to say that puts money in my pocket. But less and less money is making its way there these days. I may be for sale, but increasingly it appears as if I am “on sale” too.

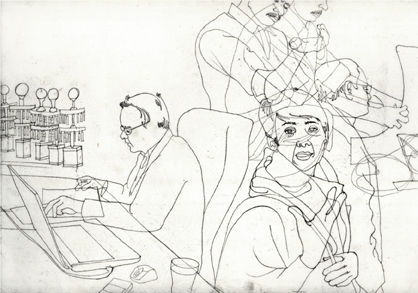

Danica Phelps. IVF in India (detail), 2008. Graphite on paper.

13 x 382.5 inches and 13 x 393 inches.

Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery (LFL).

How did this come to pass? Is it the financial crisis? No. Blaming the current economic landscape would be false, a way of displacing the truth that only my own decisions have brought me here. Here is brief breakdown of the dwindling economy of me:

- The number of words I have sold to ArtReview magazine, my regular gig (at £0.35/ word) has slowed in the past months. The magazine itself has been trimming down the number of issues it publishes, from eleven a year down to ten, and then further down to eight. Last year I earned a little more than $13,000 from my contributions to the magazine. This year will be less, not only because ArtReview is publishing fewer issues, but because the British pound has weakened against the dollar. Also, I have recently been asked to contribute 600-900 more words a month for the magazine’s website, all for no increase in my retainer.

- The position I hold at The Drawing Center in New York, Executive Editor, was once an in-house position with a fair part-time salary of $30,000 and full benefits. Very soon after I began, roughly one year ago, the economic landslide began to wash its way into U.S. cultural institutions. Budgets were “considered”; at least, this is what I take “budget considerations” to mean. I now fulfill the role of Executive Editor as an independent contractor, for half the original salary, and no benefits.

- I teach Critical Reading and Writing at Parsons, The New School for Design. Parsons has been made famous in recent years because it provides the backdrop for the wildly successful television program, Project Runway. Understandably, the school attracts students who are predominantly interested in fashion. But to suggest that these students are interested in anything seems far fetched. And few can write a grammatically correct sentence, or organize a thought on a page. Much of the faculty excuses them as “creatives.” I shepherd such students through a course that is minimally designed to teach them how to write expository prose. For this I get paid $770.32 a month.

- Four years ago, with a business partner, I began an art consulting company, Boyd Level LLC. Our company, I would say, is successful; after all, we are into our fifth year of operations. But I must also admit that it was a labor of love when we brought it into the world, and, like a hungry young child, it consumes. It has brought some dividends, and I am proud of it, but it is a long way from “taking care of me as I grow older.” I took out $9,000 last year in guaranteed payments. This year, I will likely shift to working “for” the company as an independent contractor, which will guarantee a salary of $22,200. But this comes at the price of no longer feeling—as when a child legally separates from a parent—that the company is “mine.”

This is my economic life as it stands. I write about it here not as some cathartic exercise (though perhaps it is that a little) but as an act of economic strategy. The more I write about my own economic circumstance, the more, one could say, I earn from it, because, as my circumstance, my “life” and “work” rendered as “writing,” the more it is able to earn for me.

Danica Phelps. Letters from the last list (January 24, 2007) (installation), 2008. Trash. Dimensions variable.

Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery (LFL).

There are precedents for this strategy of course. One need look no further than an artist such as Danica Phelps, whose obsessive tables and drawings track every dollar of her income and expenditures, as well as all of her “assets.” When these tables and drawings are sold, the expenditures that led to their making, which, of course, are the expenditures of Phelps’ life itself, become income once again. Images of her assets are “sold” without the assets themselves ever changing hands. There is a name for these kinds of reflected assets, one with which we have all become uncomfortably familiar as of late, and that is “derivatives.”

I want to be clear that this is in no way a statement that Phelps’ art is itself in some way “derivative.” Far from it, in fact. What Phelps’ work materializes in a very real manner is the kind of abstraction that the value-form of capitalism puts into play. That her work can take on the appearance of “abstract painting” (as did the three large panels representing her new mortgage, exhibited at Phelps’ Material Recovery show in 2008) only demonstrates how the history of abstraction, when set in relief against terms such as “representation” or “figuration,” is one that has mined a very limited understanding of just what abstraction is, or how it works, within the context of a broader political economy.

What Phelps’ work puts on display is the abstracted form of value itself, which Marx labeled “generic existence” (itself derived from Hegel’s “bad” or “spurious infinity”). What is lost in such abstractions are the specificities of lived experience, the obdurate character of things that find their legibility, their “use value,” only within and as oriented towards “a life.” The compulsiveness of Phelps’ stripes, and their visual registration of the artist’s own labor, overcome something of the generic values that they document, and so return to the artist’s economic life the inalienability of its own dignity.

This all changes, of course, with the advent of Phelps’ Stripe Factory paintings of 2008, for which the artist made use of assistants. It does not make sense to call these paintings “pure abstractions,” because they are as equally real in their representations as Phelps’ previous works. But produced at a remove from what we might call the original “Phelps Economy,” the works lose sight of their underlying asset. What is gone is any relationship to the specifics of the time and place of the “life” to which they were once linked. The Stripe Factory paintings became “mere” commodities rather than singular things; their value gets literally lost in the transfer, to the point that the artist, or the potential owner, does not really know what they are holding. Little wonder, then, that the Factory became insolvent.

Now, as I am writing this, in its self-reflexivity, I am earning more from my own economic circumstances than they have produced on their own thus far; and I will have earned something from Danica Phelps’ economic circumstances too. In writing about Phelps, I make money not from her but on her, just as in writing about me, I make money on me. But, of course, all of this earning is subject to the law of diminishing marginal returns. Which is to say, the more that I write on me, or the more that I write on Phelps, the less you, dear reader, will want to read, and the less I will be asked, and paid, to write in general. (The situation would be akin to a memoirist who writes variations on the same book over and over again; or then again, and perhaps worse, to an art critic who reviews the same show, month after month.)

As we can see, it is the law of diminishing returns that demands novelty. It demands a new way of writing about and a new way of making (or conceiving of or thinking about) art. But more generally, it demands change. This may sound like a cliché, but it is what my own very real (diminished and diminishing) economic circumstances have crystallized for me. And perhaps instead of thinking about new ways of writing, or new ways of making art, what we really need to begin speaking and thinking about are new ways of earning. In light of that, perhaps going “on sale” is no answer at all.

#00

EDITORIAL

FROM SURREALISM TO THE DECONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

Artscape

TEXTS

THE MINIATURE AND THE MODEL, ON THE PAINTINGS OF JOCHEN KLEIN

by Douglas Ashford

FROM OUTSIDE

TO SAY OR NOT TO SAY OR SAY IT ANOTHER WAY. ULRIKE OTTINGER’S FUNNY BOOKS.

by Ángela Sánchez de Vera

VISUAL ARTICLE

FROM SURREALISM TO THE DECONSTRUCTION OF REALITY

by Dani Sanchis

FROM INSIDE

ART AND DECONSTRUCTION. CONSTRUCTION, DECONSTRUCTION AND THE PRACTICES OF CONTEMPORARY ART

by Derek Bentley

CONVERSATION

ROBBINSCHILDS. AT THE NEW MUSEUM

by Juanli Carrión

Artscape

WEB REVIEW

MADE IN OAXACA. Creating an Oaxacan ‘Other’ under multicolored tarps.

by Saúl Hernández

© 2013 Angel Orensanz Foundation

CONNECT US